Rehearsing the Rienzi Overture with the Orquesta Juvenil Regional de Falcon. 47 youngsters from the state, were selected as part of the National’s Children’s Orchestra of Venezuela that debuted last year under Maestro Simon Rattle. One of my favorite youth orchestras of El Sistema in Venezuela.

Viewing: El Sistema Diary - View all posts

El Sistema Diary: Servant Leadership

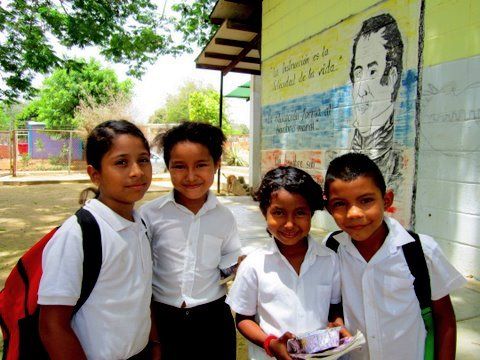

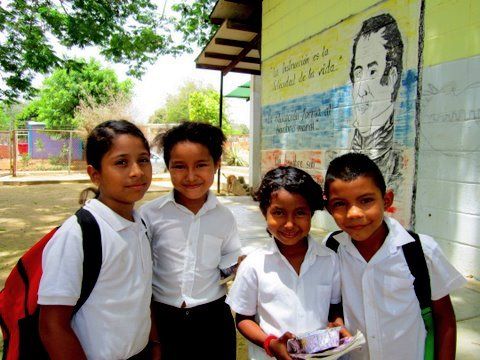

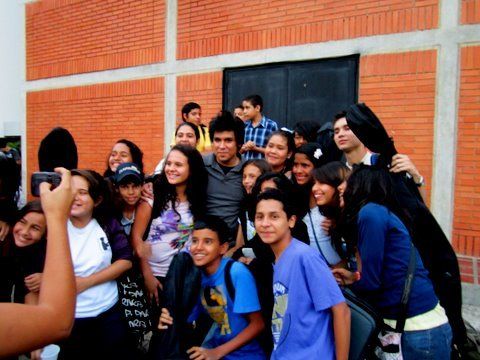

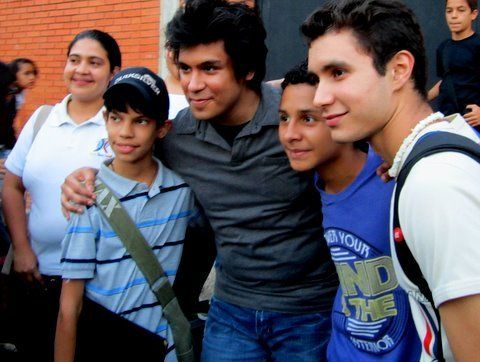

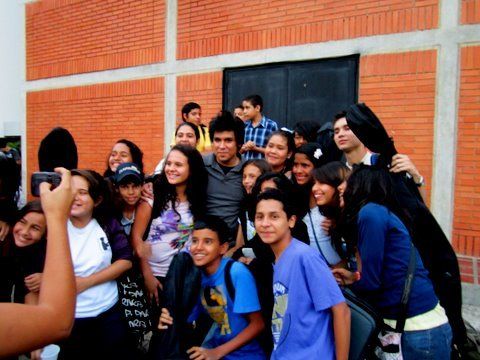

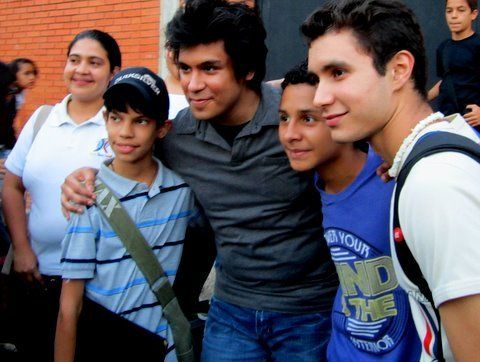

Barrio Las Panelas, is one of Coro’s most perilous areas of town. We are told there is an implicit curfew, no one is to roam the streets alone after six. Jose Maiolino, El Sistema’s courageous founder and leader for the state of Falcon, has invited us to visit a nucleo there. It is based out of a humble home, an unassuming space, re-imagined for music.

As soon as the Fellows walked in, a group of thirty young musicians began playing a German Dance. It was a beautiful welcome. They played from memory, focusing and sculpting every note. At year one, their sound is characteristically El Sistema. The string players are following on a tradition of playing stemming all the way to Maestro Abreu’s own original concept of sound, I am told. A smaller, beginner equivalent of the Simon Bolivar Orchestra of Venezuela; they too have developed a keen sense of ownership and pride, in and through their playing. Isandra Campos, the nucleo’s founder is no stranger to El Sistema. Her daughter, Ana, is a member of the Teresa Carreno Youth Orchestra of Venezuela, the program’s flagship high-school level orchestra.

Their conductor, Gerardo Reyes, a trumpet player, is one of those directores brillantisimos planted across the country that Maestro Abreu often speaks about. A young music director: part musician, part social worker. And member of a larger group of musicians that grew up in the movement, and now charged with added responsibilities of sustaining and expanding El Sistema in Venezuela. It is not an easy job, yet amid dire working conditions, he leads from the heart. "We will soon be playing the Telemann Concerto with our own in-house violist." "In less than three years, we shall do Beethoven's Fifth," he says.

Because they lack music stands, his children play, literally, by heart. That is by no means a deterrent for learning. On the contrary, it is another reason not to give up on the dream of playing well together. To them music is always about joy and that same feeling is never dependent upon having enough material resources, but rather, built upon the idea that through music an entire community may see themselves blossom and become enraptured in a state of continual perseverance. Being, not being, as Maestro Abreu describes.

Gerardo knows that many of his children come from the poorest strata of society, many of them have never met their own parents. Because he is deeply committed to a mission of social rescue through music, there are no limits to what he can produce with the youngsters. “A nucleo is an engine for societal change,” says Teresa Hernandez, another brilliant maestra: a former politician, and trainer of conductors as artists and social changers for the national movement. “A children’s orchestra conductor does only conduct music, but rather actively constructs and models new paths for success.” “He listens intently; finds the balance between intonation and rhythm, corrects posture. In doing so, the conductor also helps introduce social values to catalyze new life trajectories; he makes students feel proud about themselves.” A conductor is part of the engine of El Sistema. He leads the pedagogical planning and acts as a fervient advocate for artistic excellence and social change. She must be, at all times, inside and outside the music: playing ambassador, organizing parent meetings, raising funds, and motivating students to succeed.

At Valle de la Pascua, Christian Leal, a seventeen-year-old percussionist in my rehearsals of Tchaikovsky played with an distinctive intensity and commitment to the score. In many ways, he also led the orchestra, with me. It was no surprise that later that week, I would hear him lead a sublime performance of merengues and joropos realized with utmost brilliance. His musicians: eight gifted instrumentalists with diverse and critical special needs. Christian is using his musical talent to conduct lives. El Sistema has propelled him to see himself responsible for the growth of his peers and the development of his own community-at-large.

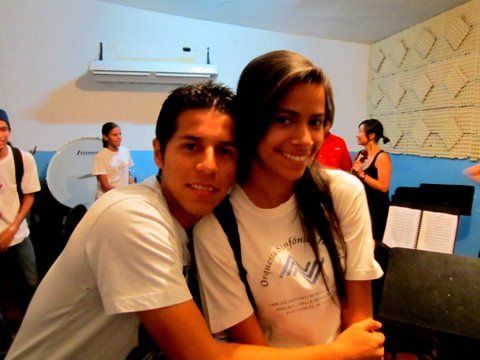

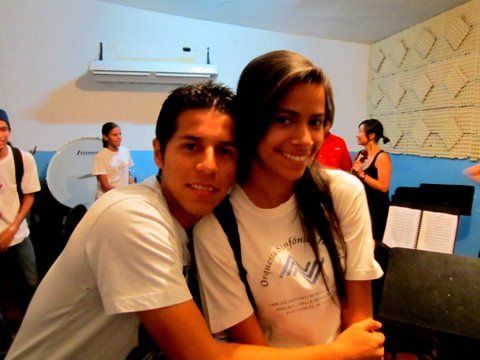

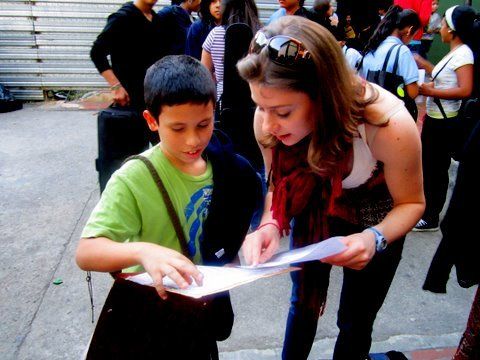

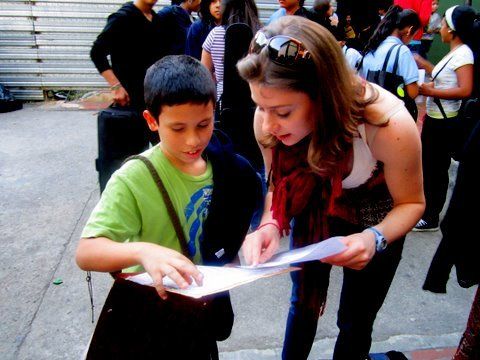

At the main nucleo in Coro, just before my rehearsal of Beethoven and Wagner with the regional youth orchestra there, I found, tucked in a quiet corner of a courtyard, a group of very young instrumentalists playing recorders being led by a charismatic young girl. I approached her and asked, are you their teacher? "Yes, I am helping them learn their music,” she replied. I managed to pass-along to her some ideas for leading ensembles, and she quickly absorbed many of the concepts. She then began by counting off with confident aplomb, three-and-play! At ten-years-old she is a natural leader, it was a joy to see her teach and give so much to her own peers. In Barquisimeto, Chacin, the talented teenage concertmaster of the Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil Franco Medina, spends her free afternoons working at Santa Rosa, a brand new nucleo just outside of the city. She drills her young students in scales, arpeggios, and exercises leading to mastering the orchestra’s weekly repertoire of arrangements of pieces from the masters. She is an extraordinary musician and a role model. Because she grew up in El Sistema, she naturally knows how to embody and enact the mission to the core. And she enjoys teaching, it is an honor for advanced students to do so.

These stories give us a hopeful glimpse into the future of El Sistema. Seeing young musical leaders in action, expressing a profound love for music and the communities they serve, give us an opportunity to experience the mission well beyond the rhetoric and at its fullest potential. It is clear that El Sistema lives within a space of actionable compassion and transferable servant leadership. Giving young people an opportunity to lead is part of the secret to success. It also motivates them to grow and thrive both as musicians and citizens.

As soon as the Fellows walked in, a group of thirty young musicians began playing a German Dance. It was a beautiful welcome. They played from memory, focusing and sculpting every note. At year one, their sound is characteristically El Sistema. The string players are following on a tradition of playing stemming all the way to Maestro Abreu’s own original concept of sound, I am told. A smaller, beginner equivalent of the Simon Bolivar Orchestra of Venezuela; they too have developed a keen sense of ownership and pride, in and through their playing. Isandra Campos, the nucleo’s founder is no stranger to El Sistema. Her daughter, Ana, is a member of the Teresa Carreno Youth Orchestra of Venezuela, the program’s flagship high-school level orchestra.

Their conductor, Gerardo Reyes, a trumpet player, is one of those directores brillantisimos planted across the country that Maestro Abreu often speaks about. A young music director: part musician, part social worker. And member of a larger group of musicians that grew up in the movement, and now charged with added responsibilities of sustaining and expanding El Sistema in Venezuela. It is not an easy job, yet amid dire working conditions, he leads from the heart. "We will soon be playing the Telemann Concerto with our own in-house violist." "In less than three years, we shall do Beethoven's Fifth," he says.

Because they lack music stands, his children play, literally, by heart. That is by no means a deterrent for learning. On the contrary, it is another reason not to give up on the dream of playing well together. To them music is always about joy and that same feeling is never dependent upon having enough material resources, but rather, built upon the idea that through music an entire community may see themselves blossom and become enraptured in a state of continual perseverance. Being, not being, as Maestro Abreu describes.

Gerardo knows that many of his children come from the poorest strata of society, many of them have never met their own parents. Because he is deeply committed to a mission of social rescue through music, there are no limits to what he can produce with the youngsters. “A nucleo is an engine for societal change,” says Teresa Hernandez, another brilliant maestra: a former politician, and trainer of conductors as artists and social changers for the national movement. “A children’s orchestra conductor does only conduct music, but rather actively constructs and models new paths for success.” “He listens intently; finds the balance between intonation and rhythm, corrects posture. In doing so, the conductor also helps introduce social values to catalyze new life trajectories; he makes students feel proud about themselves.” A conductor is part of the engine of El Sistema. He leads the pedagogical planning and acts as a fervient advocate for artistic excellence and social change. She must be, at all times, inside and outside the music: playing ambassador, organizing parent meetings, raising funds, and motivating students to succeed.

At Valle de la Pascua, Christian Leal, a seventeen-year-old percussionist in my rehearsals of Tchaikovsky played with an distinctive intensity and commitment to the score. In many ways, he also led the orchestra, with me. It was no surprise that later that week, I would hear him lead a sublime performance of merengues and joropos realized with utmost brilliance. His musicians: eight gifted instrumentalists with diverse and critical special needs. Christian is using his musical talent to conduct lives. El Sistema has propelled him to see himself responsible for the growth of his peers and the development of his own community-at-large.

At the main nucleo in Coro, just before my rehearsal of Beethoven and Wagner with the regional youth orchestra there, I found, tucked in a quiet corner of a courtyard, a group of very young instrumentalists playing recorders being led by a charismatic young girl. I approached her and asked, are you their teacher? "Yes, I am helping them learn their music,” she replied. I managed to pass-along to her some ideas for leading ensembles, and she quickly absorbed many of the concepts. She then began by counting off with confident aplomb, three-and-play! At ten-years-old she is a natural leader, it was a joy to see her teach and give so much to her own peers. In Barquisimeto, Chacin, the talented teenage concertmaster of the Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil Franco Medina, spends her free afternoons working at Santa Rosa, a brand new nucleo just outside of the city. She drills her young students in scales, arpeggios, and exercises leading to mastering the orchestra’s weekly repertoire of arrangements of pieces from the masters. She is an extraordinary musician and a role model. Because she grew up in El Sistema, she naturally knows how to embody and enact the mission to the core. And she enjoys teaching, it is an honor for advanced students to do so.

These stories give us a hopeful glimpse into the future of El Sistema. Seeing young musical leaders in action, expressing a profound love for music and the communities they serve, give us an opportunity to experience the mission well beyond the rhetoric and at its fullest potential. It is clear that El Sistema lives within a space of actionable compassion and transferable servant leadership. Giving young people an opportunity to lead is part of the secret to success. It also motivates them to grow and thrive both as musicians and citizens.

El Sistema Diary: A National Endeavor

Ask any taxi driver in Calabozo to take you to the orchestra and he will usher you straight to the right place (no address needed). Almost everyone, in large and small towns alike, knows where music is taking place. “Thank you for teaching our youngsters,” I’ve heard. I quickly tell my driver that most of the time, they are teaching me, and that it is an honor to be here. In Venezuela, orchestras and choirs often manifest themselves as an extension of civic life. An emblem of national culture indeed.

Yesterday, on national television, a few hundred children were featured singing Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand. With ribbons and their national colors wrapped around their necks, they sang with elation before the eyes of an entire nation. I doubt that Gustav Mahler would have ever imagined that his music would be sung by children in Venezuela; or that performances taking place here today would set new artistic standards--for generations to come.

Led by their own Gustavo, the youngsters sang in precise counterpoint against the voices of two iconic professional orchestras (the LA Phil and the Simon Bolivar, the pride of Venezuela). During the broadcast, at a local restaurant, we saw a group people gravitate towards the television set, fascinated by the sight of the event. I would imagine it meant something quite special to have seen a representation of their national youth singing with such agreeable intention. I met some of these young choristers here in Guarico. Led by Manuel Lopez, they prepared their parts, working in Caracas intensively for more than two weeks. “It was the experience of a lifetime,“ they told me.

During my rehearsal with the children’s orchestra at the Antonio Estevez nucleo (named after the composer of Cantata Criolla) we set out to conquer their first reading of Venezuela, a piece that is very often played by similar groups throughout the country. Scored for an intermediate level symphony orchestra, it is in many ways, the equivalent of a national anthem. It has that kind of singular resonance to it. The melody is strikingly emotive.

Delving into our work, I thanked the children for allowing me to lead them in such a uniquely national piece. As we began solving some of the technical issues inherent in the score, we paid attention to balancing the voices. Let us hear the woodwinds soar above the strings, the trumpets need a more rounded sound, I requested. Equally important here was to ask what kind of emotions may we derive from the music that we chose to play, and for what end?

“It is a piece from my homeland, Venezuela,” a young double-bassist shouted with a decisive flair. “The piece should reflect a feeling of joy, and pride, and also love,” the students remarked. The children agreed that it should reflect aspects of their own lives. “Do you have any similar pieces from your own country,” they asked in return. The works of Jose Pablo Moncayo and Aaron Copland reflect the musical tradition of the countries I grew up in, I said.

My colleague, Julie, sitting in the viola section and also team teaching with me (a signature El Sistema practice) played us an excerpt of America the Beautiful. The children listened attentively, focusing on every note. A sign of their ability to play ambassadors and of their deeper understanding for the finer nuances of musical collaboration.

Musicians from El Sistema are deeply connected to a spirit of community and nationalism. As they grow up together, their fellow musicians become, in many ways, part of their own family. And they are part of a national family as well. Clearly, its many participants feel music as something that is larger than themselves.

Pieces like Venezuela are heard everywhere: in orchestral and choral settings. They are also meant to be played for a lifetime. Because these pieces bring forth experiences of unity and source of national pride, they are often played, and remain a staple of the academic curriculum and graded repertoire.

Folk music is also being introduced. In Guarico, the alma llanera (soul of the plains) movement, begun about nine years ago, has sprung up in cities around the state, producing a few hundred folk musicians playing cuatros, maracas, bandolas, and harps. Their hope is to bring these instruments to an academic or conservatory level status, where they may be fully accepted and appreciated as part of a “legitimate art form.” Recently, Gustavo Dudamel was heard conducting a folk ensemble (seated as a traditional orchestra) for the celebration of his country’s bicentennial. A national hero himself, he is also the subject of a colorful tile mural, just outside of his home nucleo in Barquisimeto, where out of his hand, stems a swirling national flag--a metaphor for nationalism at the heart of El Sistema.

These iconic representations, may also give us an insight into the way music-making may be envisioned. The Simon Bolivar Orchestra, El Sistema’s flagship ensemble (now a fully professional orchestra), is aptly named after the country’s revered founding father. His words are often evoked in schools, “an uneducated citizen, is an incomplete being,” inscriptions a top blackboards read.

The Simon Bolivar, is the most finished product of El Sistema. It is also the program’s most prominent ambassador, playing around the world a universal repertoire of Stravinsky, Beethoven, and Marquez with an intention that is clearly national in that the orchestra reflects not only their own collective success as musicians but that of an entire musical movement. Many children aspire to be in this orchestra. “Landing a spot there may be the equivalent of making the roster for the Olympic team,” students have told me.

El Sistema is decisively a national endeavor. The most viable option for music learning in the country, it remains a venerated staple for humanist education and a guiding light for thousands of its participants. It is both a social and an artistic program at the same time, embracing everyone who may be willing to contribute to making music together. It is not exclusive to underserved children, on the contrary, it brings an entire population of students reflecting all strata of Venezuelan society.

Music is changing lives. But most importantly, it is helping create a culture of collaboration, where the youngest voices of a nation are valued, cultured, and recognized as a source of pride, ushering in, new ideals for the shaping of a developing nation. At the end of our final rehearsal today, Venezuela sounded, beautifully. The children chanted, “si se pudo” (yes we could). We made it happen together.

Yesterday, on national television, a few hundred children were featured singing Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand. With ribbons and their national colors wrapped around their necks, they sang with elation before the eyes of an entire nation. I doubt that Gustav Mahler would have ever imagined that his music would be sung by children in Venezuela; or that performances taking place here today would set new artistic standards--for generations to come.

Led by their own Gustavo, the youngsters sang in precise counterpoint against the voices of two iconic professional orchestras (the LA Phil and the Simon Bolivar, the pride of Venezuela). During the broadcast, at a local restaurant, we saw a group people gravitate towards the television set, fascinated by the sight of the event. I would imagine it meant something quite special to have seen a representation of their national youth singing with such agreeable intention. I met some of these young choristers here in Guarico. Led by Manuel Lopez, they prepared their parts, working in Caracas intensively for more than two weeks. “It was the experience of a lifetime,“ they told me.

During my rehearsal with the children’s orchestra at the Antonio Estevez nucleo (named after the composer of Cantata Criolla) we set out to conquer their first reading of Venezuela, a piece that is very often played by similar groups throughout the country. Scored for an intermediate level symphony orchestra, it is in many ways, the equivalent of a national anthem. It has that kind of singular resonance to it. The melody is strikingly emotive.

Delving into our work, I thanked the children for allowing me to lead them in such a uniquely national piece. As we began solving some of the technical issues inherent in the score, we paid attention to balancing the voices. Let us hear the woodwinds soar above the strings, the trumpets need a more rounded sound, I requested. Equally important here was to ask what kind of emotions may we derive from the music that we chose to play, and for what end?

“It is a piece from my homeland, Venezuela,” a young double-bassist shouted with a decisive flair. “The piece should reflect a feeling of joy, and pride, and also love,” the students remarked. The children agreed that it should reflect aspects of their own lives. “Do you have any similar pieces from your own country,” they asked in return. The works of Jose Pablo Moncayo and Aaron Copland reflect the musical tradition of the countries I grew up in, I said.

My colleague, Julie, sitting in the viola section and also team teaching with me (a signature El Sistema practice) played us an excerpt of America the Beautiful. The children listened attentively, focusing on every note. A sign of their ability to play ambassadors and of their deeper understanding for the finer nuances of musical collaboration.

Musicians from El Sistema are deeply connected to a spirit of community and nationalism. As they grow up together, their fellow musicians become, in many ways, part of their own family. And they are part of a national family as well. Clearly, its many participants feel music as something that is larger than themselves.

Pieces like Venezuela are heard everywhere: in orchestral and choral settings. They are also meant to be played for a lifetime. Because these pieces bring forth experiences of unity and source of national pride, they are often played, and remain a staple of the academic curriculum and graded repertoire.

Folk music is also being introduced. In Guarico, the alma llanera (soul of the plains) movement, begun about nine years ago, has sprung up in cities around the state, producing a few hundred folk musicians playing cuatros, maracas, bandolas, and harps. Their hope is to bring these instruments to an academic or conservatory level status, where they may be fully accepted and appreciated as part of a “legitimate art form.” Recently, Gustavo Dudamel was heard conducting a folk ensemble (seated as a traditional orchestra) for the celebration of his country’s bicentennial. A national hero himself, he is also the subject of a colorful tile mural, just outside of his home nucleo in Barquisimeto, where out of his hand, stems a swirling national flag--a metaphor for nationalism at the heart of El Sistema.

These iconic representations, may also give us an insight into the way music-making may be envisioned. The Simon Bolivar Orchestra, El Sistema’s flagship ensemble (now a fully professional orchestra), is aptly named after the country’s revered founding father. His words are often evoked in schools, “an uneducated citizen, is an incomplete being,” inscriptions a top blackboards read.

The Simon Bolivar, is the most finished product of El Sistema. It is also the program’s most prominent ambassador, playing around the world a universal repertoire of Stravinsky, Beethoven, and Marquez with an intention that is clearly national in that the orchestra reflects not only their own collective success as musicians but that of an entire musical movement. Many children aspire to be in this orchestra. “Landing a spot there may be the equivalent of making the roster for the Olympic team,” students have told me.

El Sistema is decisively a national endeavor. The most viable option for music learning in the country, it remains a venerated staple for humanist education and a guiding light for thousands of its participants. It is both a social and an artistic program at the same time, embracing everyone who may be willing to contribute to making music together. It is not exclusive to underserved children, on the contrary, it brings an entire population of students reflecting all strata of Venezuelan society.

Music is changing lives. But most importantly, it is helping create a culture of collaboration, where the youngest voices of a nation are valued, cultured, and recognized as a source of pride, ushering in, new ideals for the shaping of a developing nation. At the end of our final rehearsal today, Venezuela sounded, beautifully. The children chanted, “si se pudo” (yes we could). We made it happen together.

El Sistema Diary: Finding Purpose

At Valle de la Pascua, a small rural town in the heart of Venezuela, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet never sounded so endearing to me. It is a score that is undeniably compelling: lyrical and dramatic--the story of two star-crossed lovers, one that we know almost too well. In our rehearsal, I asked the students to imagine themselves in the story of the music and to throw themselves freely into the drama of the Shakespearian narrative.

Without hesitation, the musicians quickly became absorbed by the music. I was also taken with them, in an exchange that allowed the orchestra members to communicate among themselves freely and passionately, in and through the music. During our rehearsal, the electricity went out. The orchestra didn’t miss a beat. For a moment, we continued in darkness, finding our way back to the dimly lit room. Here again, it was not about finding perfection, but rather, finding purpose.

El Sistema in Venezuela has fashioned persuasive paradigms for the rationale and purpose of art. Music is never seen as a luxury, but rather as a natural extension of a young person’s life. In Mahomito, a humble elementary school just a few miles away from our home base, we heard a group of choristers singing a repertoire of boleros, merengues, and musica llanera (songs from the Venezuelan plains).

I saw young children holding hands, feeling every nuance in the songs, and cherishing the splendor of their doing something well together. Many of them immersed in the musical experience, eyes closed, as if somehow they had found their own sanctuary of peace. They were proud to perform for us.

Very few times have I experienced such powerful music-making. In their performance, I heard a new kind of intention and aesthetic of sound. Their music in two-part harmony juxtaposed by the energetic strumming of a cuatro, shined with palpable relevance, illuminating the crowded rehearsal room, bringing many of us to tears. What made their performance so moving?

I couldn’t help but to think about the children’s own life stories. Why do they sing? Why does it matter so much? It is clear to me that the children of El Sistema sing and play because it brings them to a world of tangible opportunity, giving them a new sense of unencumbered freedom that allows them to express themselves.

Music serves as an instrument for social transformation in that it adds concrete value to their lives, providing for new perspectives, amid the challenges that they may encounter where they reside (where more often than not, the living conditions are precarious on many levels). In a space where opportunities are scarce, music is the conduit for striving for a better life. And this is why every note might be purposefully and intentionally defined with a unique texture, colored with a sense of urgency and care at the same time.

In an orchestra or a choir, participants blossom through the sharing of profound artistic experiences and the rendering of beauty through collaboration (a theme that has been consistent throughout my immersion into El Sistema in Venezuela). In pursuing music, students generate a level of motivation that leads to re-imagining a new intention for life, creating both improved social environments and poignant music-making experiences. This framework gives us a new aesthetic of possibility where students’ capacity for growth is extended as far as the universe of music. It is only up to each individual to decide how far they may choose to go.

Without hesitation, the musicians quickly became absorbed by the music. I was also taken with them, in an exchange that allowed the orchestra members to communicate among themselves freely and passionately, in and through the music. During our rehearsal, the electricity went out. The orchestra didn’t miss a beat. For a moment, we continued in darkness, finding our way back to the dimly lit room. Here again, it was not about finding perfection, but rather, finding purpose.

El Sistema in Venezuela has fashioned persuasive paradigms for the rationale and purpose of art. Music is never seen as a luxury, but rather as a natural extension of a young person’s life. In Mahomito, a humble elementary school just a few miles away from our home base, we heard a group of choristers singing a repertoire of boleros, merengues, and musica llanera (songs from the Venezuelan plains).

I saw young children holding hands, feeling every nuance in the songs, and cherishing the splendor of their doing something well together. Many of them immersed in the musical experience, eyes closed, as if somehow they had found their own sanctuary of peace. They were proud to perform for us.

Very few times have I experienced such powerful music-making. In their performance, I heard a new kind of intention and aesthetic of sound. Their music in two-part harmony juxtaposed by the energetic strumming of a cuatro, shined with palpable relevance, illuminating the crowded rehearsal room, bringing many of us to tears. What made their performance so moving?

I couldn’t help but to think about the children’s own life stories. Why do they sing? Why does it matter so much? It is clear to me that the children of El Sistema sing and play because it brings them to a world of tangible opportunity, giving them a new sense of unencumbered freedom that allows them to express themselves.

Music serves as an instrument for social transformation in that it adds concrete value to their lives, providing for new perspectives, amid the challenges that they may encounter where they reside (where more often than not, the living conditions are precarious on many levels). In a space where opportunities are scarce, music is the conduit for striving for a better life. And this is why every note might be purposefully and intentionally defined with a unique texture, colored with a sense of urgency and care at the same time.

In an orchestra or a choir, participants blossom through the sharing of profound artistic experiences and the rendering of beauty through collaboration (a theme that has been consistent throughout my immersion into El Sistema in Venezuela). In pursuing music, students generate a level of motivation that leads to re-imagining a new intention for life, creating both improved social environments and poignant music-making experiences. This framework gives us a new aesthetic of possibility where students’ capacity for growth is extended as far as the universe of music. It is only up to each individual to decide how far they may choose to go.

El Sistema Diary: A Relentless Work Ethic

El Sistema orchestras in Venezuela excel in many aspects, yet one of their most remarkable collective triumphs is their relentless work ethic. This week, I worked with the Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil Franco Medina on Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. It was a four hour rehearsal. After we had become acclimated with each other I asked, when it would be appropriate to have a short break. They all said, “we don’t need a break, let’s keep going.”

This group is usually composed of musicians ages ranging thirteen to fifteen. They have come out of El Sistema Lara’s systematic approach to graduated orchestral instruction (this is the fourth orchestra in the program’s through line). Their ability to embrace musical goals with utmost diligence and curiosity is part of what makes their sound come alive so readily. It is how they advance so quickly, from arrangements of Marche Slave to Mahler Symphonies, in just a few years.

At this stage, they already understand the culture of playing in an orchestra, the aesthetics of sound; and they are also very focused on learning repertoire, quickly, at a much faster rate than their predecessors. This is why it isn’t surprising to see children’s orchestras playing complete Mahler symphonies in Caracas. The system has produced a long lineage of best practices and tools for talent development.

Learning is happening at a dramatic pace, because the children have insightful role models to look up to. The artistic prowess of El Sistema is carefully documented, young people can see and hear on YouTube what the Teresa Carreno Youth Orchestra (the most advanced high school age ensemble) is playing and how they are playing it. In Barquisimeto, while playing Marquez’s Danzon No. 2, many young violinists even emulate the motions of Lila Vivas (the orchestra’s concertmaster) as they go through the piece.

Here, I met an extremely gifted musician, who is learning to conduct the repertoire of his own children’s orchestra by watching other conductors work on the same repertoire with similar orchestras around the country. “I take the scores and conduct while the video plays, that’s how I can learn the music, says Jose Victor, a twelve-year-old horn player. Even during our rehearsal, it was easier to describe a specific bowing and articulation of sound, by pointing out directly to a certain viral performance by the Orquesta Infantil de Caracas.

Every musician in El Sistema is connected, they are all growing together. They all aspire together.

And that culture of aspiration manifests in many different ways. Motivation is key. It is part of the ethos of El Sistema. Frank Enrique, a clarinet player at my rehearsal, travels from Tamaca to Barquisimeto every day to attend his orchestra sessions. On a good day, it may take about two hours, each way. He is learning Shostakovich’s tenth symphony, it is a part of a major audition, leading to his dream of playing in of Caracas’ finest youth orchestras. Not everyone is centered on these artistic goals, many are here because they just “want to make new friends.”

A careful balance of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is part of the ingredients of their unyielding work ethic. In El Sistema, there are very clear artistic objectives in place. It is part of a goal setting theory where a level of success is achieved on a daily basis.

As we worked on the Tchaikovsky, we centered on building a musical narrative built on a variety of moods. Tempo changes had to be worked out between sections, but most importantly, the emotional aspects of the episodes had to be realized through a sense of collective understanding of a feeling for the music. We didn’t focus as much on having a technically perfect performance. That will come, with time. The main idea is to create a space of creative immersion and tap on the student’s potential for collaboration.

In El Sistema, there are no limits to the music-making, because peer-to-peer relationships developed in and through the orchestra take on multiple meanings and hence, artistic form. The music becomes larger than life. Individual skills are refined purposefully, for the benefit of the collective whole. The orchestra is the great motivator.

Because El Sistema has been built upon an upward spiral of motivation, student’s work with tenacious commitment. There are many different layers of goal setting embedded in the El sistema culture. Everyone: students, teachers, and the community at large, has a particular role and part to play. In the end, every performance is a manifestation of something that is much larger than the music itself. There are no other special ingredient here. It is hard work, that drives such extraordinary artistic achievements.

A short clip from our rehearsals this week.

This group is usually composed of musicians ages ranging thirteen to fifteen. They have come out of El Sistema Lara’s systematic approach to graduated orchestral instruction (this is the fourth orchestra in the program’s through line). Their ability to embrace musical goals with utmost diligence and curiosity is part of what makes their sound come alive so readily. It is how they advance so quickly, from arrangements of Marche Slave to Mahler Symphonies, in just a few years.

At this stage, they already understand the culture of playing in an orchestra, the aesthetics of sound; and they are also very focused on learning repertoire, quickly, at a much faster rate than their predecessors. This is why it isn’t surprising to see children’s orchestras playing complete Mahler symphonies in Caracas. The system has produced a long lineage of best practices and tools for talent development.

Learning is happening at a dramatic pace, because the children have insightful role models to look up to. The artistic prowess of El Sistema is carefully documented, young people can see and hear on YouTube what the Teresa Carreno Youth Orchestra (the most advanced high school age ensemble) is playing and how they are playing it. In Barquisimeto, while playing Marquez’s Danzon No. 2, many young violinists even emulate the motions of Lila Vivas (the orchestra’s concertmaster) as they go through the piece.

Here, I met an extremely gifted musician, who is learning to conduct the repertoire of his own children’s orchestra by watching other conductors work on the same repertoire with similar orchestras around the country. “I take the scores and conduct while the video plays, that’s how I can learn the music, says Jose Victor, a twelve-year-old horn player. Even during our rehearsal, it was easier to describe a specific bowing and articulation of sound, by pointing out directly to a certain viral performance by the Orquesta Infantil de Caracas.

Every musician in El Sistema is connected, they are all growing together. They all aspire together.

And that culture of aspiration manifests in many different ways. Motivation is key. It is part of the ethos of El Sistema. Frank Enrique, a clarinet player at my rehearsal, travels from Tamaca to Barquisimeto every day to attend his orchestra sessions. On a good day, it may take about two hours, each way. He is learning Shostakovich’s tenth symphony, it is a part of a major audition, leading to his dream of playing in of Caracas’ finest youth orchestras. Not everyone is centered on these artistic goals, many are here because they just “want to make new friends.”

A careful balance of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is part of the ingredients of their unyielding work ethic. In El Sistema, there are very clear artistic objectives in place. It is part of a goal setting theory where a level of success is achieved on a daily basis.

As we worked on the Tchaikovsky, we centered on building a musical narrative built on a variety of moods. Tempo changes had to be worked out between sections, but most importantly, the emotional aspects of the episodes had to be realized through a sense of collective understanding of a feeling for the music. We didn’t focus as much on having a technically perfect performance. That will come, with time. The main idea is to create a space of creative immersion and tap on the student’s potential for collaboration.

In El Sistema, there are no limits to the music-making, because peer-to-peer relationships developed in and through the orchestra take on multiple meanings and hence, artistic form. The music becomes larger than life. Individual skills are refined purposefully, for the benefit of the collective whole. The orchestra is the great motivator.

Because El Sistema has been built upon an upward spiral of motivation, student’s work with tenacious commitment. There are many different layers of goal setting embedded in the El sistema culture. Everyone: students, teachers, and the community at large, has a particular role and part to play. In the end, every performance is a manifestation of something that is much larger than the music itself. There are no other special ingredient here. It is hard work, that drives such extraordinary artistic achievements.

A short clip from our rehearsals this week.

El Sistema Diary: The Spirit of Music

Santa Rosa, a picturesque colonial town, just outside of Barquisimeto, is the home to La Divina Pastora, Venezuela‘s most revered Saint Patroness. Just over two years ago, a nucleo was started there, at the heart of community. Literally, classes take place outside, around the main square, in homes, at the jefatura (mayor‘s office), parochial classrooms--all within a close perimeter. Music is heard in and around every corner. José Luis Giménez, the nucleo’s decisive founder says, “wherever there is a shade, there is music.”

They are slowly building their nucleo. There are five hundred students enrolled: two orchestras playing arrangements of Dvorak’s Ninth Symphony, choirs, and a recently formed cello ensemble. “We are imploring to the Virgin that we may have an adequate space for teaching.“ “I know it will come,“ says Giménez.

Plans to build an official rehearsal space are underway. Carmen, a parent, is an architect and has donated her services to render a model and blueprint. It will be a modest space that will overlook the Turbia Valley and the verdant hills around Barquisimeto--music amid a pastoral setting.

Things start slowly, they take time.

The students also want to make a case for themselves. They are working towards producing a concert at La Sede, home of the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra. They want to be heard. Their energy is contagious, their sound enormous. Music matters to them. They aspire to reach new realms of achievement, every single day. The orchestra is a serious commitment for both the students and their families.

To see the beginnings of a process where an entire town is being transformed by and through music is indeed, very special. Here, El Sistema is framing the arts as a conduit for social development of the highest order. Their orchestra is an asset, a tool for building social capital; elevating their quality of life through a constant exposure to beauty.

The main square, a hub for music, has also become a place of peace, guided by the gracious spirit of La Divina Pastora, who watches over the orchestra and those who take part in it.

Wherever there is music, there is also hope.

They are slowly building their nucleo. There are five hundred students enrolled: two orchestras playing arrangements of Dvorak’s Ninth Symphony, choirs, and a recently formed cello ensemble. “We are imploring to the Virgin that we may have an adequate space for teaching.“ “I know it will come,“ says Giménez.

Plans to build an official rehearsal space are underway. Carmen, a parent, is an architect and has donated her services to render a model and blueprint. It will be a modest space that will overlook the Turbia Valley and the verdant hills around Barquisimeto--music amid a pastoral setting.

Things start slowly, they take time.

The students also want to make a case for themselves. They are working towards producing a concert at La Sede, home of the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra. They want to be heard. Their energy is contagious, their sound enormous. Music matters to them. They aspire to reach new realms of achievement, every single day. The orchestra is a serious commitment for both the students and their families.

To see the beginnings of a process where an entire town is being transformed by and through music is indeed, very special. Here, El Sistema is framing the arts as a conduit for social development of the highest order. Their orchestra is an asset, a tool for building social capital; elevating their quality of life through a constant exposure to beauty.

The main square, a hub for music, has also become a place of peace, guided by the gracious spirit of La Divina Pastora, who watches over the orchestra and those who take part in it.

Wherever there is music, there is also hope.

El Sistema Diary: Building a Sound Culture

In Barquisimeto, I asked a student what made the Venezuelan orchestras play with such inspiration. “They have charisma,” he said. Everyone brings their own self into the music, and every musician looks for new things that they can bring. “Any orchestra can play the Danzon No. 2, but we make it special, because we don’t just focus on the notes, we focus on feeling the music.”

Part of the aesthetics of sound in El Sistema stem from being the music. It is a process that is driven by both a kinesthetic and affective approach to performance. The narratives in the music, literally move the orchestras. The embedded experience-constants guide their music-making.

It is a culture of establishing relationships through sound. The fact that musicians can grow up together and make music throughout their youth allows them to discover themselves as active participants and collaborators of beauty. They can share their feelings freely and without reservation. Perfection is never the goal, striving towards something that is larger than oneself is part of the aesthetics. The music is often exaggerated, dynamic ranges are wider than usual, rhythmic passages taken on more percussive qualities, lyrical sections speak with heartfelt expression.

In El Sistema, we hear a different kind of sound, unified throughout all levels of musical skill, because their artistry encompasses an entire dimension of life experiences, reflected in and through music. As a social program, music takes on different meanings. And this helps musicians transcend both as individuals and as a community, extending the possibilites of music far beyond the notes, and into new realms of human expression.

Part of the aesthetics of sound in El Sistema stem from being the music. It is a process that is driven by both a kinesthetic and affective approach to performance. The narratives in the music, literally move the orchestras. The embedded experience-constants guide their music-making.

It is a culture of establishing relationships through sound. The fact that musicians can grow up together and make music throughout their youth allows them to discover themselves as active participants and collaborators of beauty. They can share their feelings freely and without reservation. Perfection is never the goal, striving towards something that is larger than oneself is part of the aesthetics. The music is often exaggerated, dynamic ranges are wider than usual, rhythmic passages taken on more percussive qualities, lyrical sections speak with heartfelt expression.

In El Sistema, we hear a different kind of sound, unified throughout all levels of musical skill, because their artistry encompasses an entire dimension of life experiences, reflected in and through music. As a social program, music takes on different meanings. And this helps musicians transcend both as individuals and as a community, extending the possibilites of music far beyond the notes, and into new realms of human expression.

El Sistema Diary: A New School of Social Life

At Barquisimeto, I sat down for a long conversation with Maestro Luis Jimenez, one of El Sistema’s founders and most fervient advocates. “We are living a dream,” he said. And rightly so. The nucleo was one of the first in the country. The musical home of Gustavo Dudamel, it now serves three thousand beneficiaries making-up nine youth orchestras, numerous choirs, and also special needs education programming.

I asked Maestro Jimenez, a father-like figure in the nucleo, what had made him decide to dedicate a life to teaching music for social change. “Maestro Abreu had a broad vision, from the very beginning.” “In 1975, when we started the first truly national orchestra of Venezuelans, he was already thinking about a movement. I was in the cello section, and during our rehearsals, he incessantly cultivated a way of forward thinking, planting seeds, and sharing the future.” The model that the orchestra had built in Caracas was meant to be replicated, many musicians began plans to build similar programs, all over the country. This wasn’t just an orchestra, it was a group of individuals who would lead change, in profound ways.

From the very beginning, the orchestra has been the framework from which El Sistema has evolved. It guides the pedagogy and all social aspects of music-making. Here, students don’t ask where you are from, but rather what orchestra you play in. You may find children playing side-by-side in between rehearsals as duos or trios, to perfect a certain passage, learning from each other. Or teenage musicians at the areperia during lunch hour, trying to make sense of a certain difficult rhythm pattern, scores in hand, in preparation for their rehearsals that evening. The orchestra is the conduit for learning and measuring achievement.

Here, in Barquisimeto, all orchestras lead to another, in a pyramid scheme, culminating in the Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil de Lara, a semi-professional orchestra that is playing Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony this same week. There is ample room for everyone here, students transfer to advancing ensembles when they are ready, no matter the age (a few 12 year-old children are playing Prokofiev). Many of them spend as many as ten years participating in the program. The majority of graduates do not become professional musicians, yet continue their education as professional in a wide-variety of careers.

Maestro Jimenez asked me to work with the Orquesta Doralisa de Medina, the pride and joy of the nucleo. This ensemble, is their student’s first opportunity to come together as a symphony orchestra, complete with woodwinds, brass, and percussion sections. We worked on arrangements by Purcell and Charpentier. Our orchestra’s timpanist, a brand new musician to the nucleo, was supported by a tallerista (an itinerant teaching-artist), playing side-by-side, a common occurrence in El Sistema.

During the rehearsal we emphasized listening to each other, to realize our instrumental voices as interdependent. How are the flutes articulating the melody? Can we match the sound with the cello section’s counterpoint? Making artistic decisions--both conductor and musicians--together, is a way to begin thinking of the orchestra as a model for dialogue and as Maestro Abreu describes it, as "a new school of social life.”

As I’ve experienced, a nucleo is about building infrastructures, not just of orchestras, but of new citizens, equipped with tools to lead change and build a more promising future of their own and in benefit of their nation’s wellbeing. Music matters, profoundly.

I asked Maestro Jimenez, a father-like figure in the nucleo, what had made him decide to dedicate a life to teaching music for social change. “Maestro Abreu had a broad vision, from the very beginning.” “In 1975, when we started the first truly national orchestra of Venezuelans, he was already thinking about a movement. I was in the cello section, and during our rehearsals, he incessantly cultivated a way of forward thinking, planting seeds, and sharing the future.” The model that the orchestra had built in Caracas was meant to be replicated, many musicians began plans to build similar programs, all over the country. This wasn’t just an orchestra, it was a group of individuals who would lead change, in profound ways.

From the very beginning, the orchestra has been the framework from which El Sistema has evolved. It guides the pedagogy and all social aspects of music-making. Here, students don’t ask where you are from, but rather what orchestra you play in. You may find children playing side-by-side in between rehearsals as duos or trios, to perfect a certain passage, learning from each other. Or teenage musicians at the areperia during lunch hour, trying to make sense of a certain difficult rhythm pattern, scores in hand, in preparation for their rehearsals that evening. The orchestra is the conduit for learning and measuring achievement.

Here, in Barquisimeto, all orchestras lead to another, in a pyramid scheme, culminating in the Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil de Lara, a semi-professional orchestra that is playing Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony this same week. There is ample room for everyone here, students transfer to advancing ensembles when they are ready, no matter the age (a few 12 year-old children are playing Prokofiev). Many of them spend as many as ten years participating in the program. The majority of graduates do not become professional musicians, yet continue their education as professional in a wide-variety of careers.

Maestro Jimenez asked me to work with the Orquesta Doralisa de Medina, the pride and joy of the nucleo. This ensemble, is their student’s first opportunity to come together as a symphony orchestra, complete with woodwinds, brass, and percussion sections. We worked on arrangements by Purcell and Charpentier. Our orchestra’s timpanist, a brand new musician to the nucleo, was supported by a tallerista (an itinerant teaching-artist), playing side-by-side, a common occurrence in El Sistema.

During the rehearsal we emphasized listening to each other, to realize our instrumental voices as interdependent. How are the flutes articulating the melody? Can we match the sound with the cello section’s counterpoint? Making artistic decisions--both conductor and musicians--together, is a way to begin thinking of the orchestra as a model for dialogue and as Maestro Abreu describes it, as "a new school of social life.”

As I’ve experienced, a nucleo is about building infrastructures, not just of orchestras, but of new citizens, equipped with tools to lead change and build a more promising future of their own and in benefit of their nation’s wellbeing. Music matters, profoundly.

El Sistema Diary: The Aesthetics of Generosity

At La Sede, young musicians were invited to listen in to Deutsche Grammophon's recording session of the Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra under Gustavo Dudamel. Sitting in the front rows, the children were attentive to the orchestra’s every sound and nuance. Seeing them all there, at such an important and historic ocassion--listening, describing, and embracing the music-making--was a beautiful experience.

We were all captivated by the performance. Over the years, the orchestra has grown to acquire a unique personality and palpable charisma. Beethoven was pushed to the limits. The Eroica lived and breathed in a space of increasingly wider dynamic ranges and more expansive phrases, always emphasizing the ground-breaking essence of the old-age narrative. It will be a recording that will generate a lot of interest among classical music enthusiasts.

One could readily feel Beethoven’s sense of angst and despair, of heroism and possibility. Today, Gustavo Dudamel and his orchestra took on the role of heroes, relating stories of passion and possibility to us all, and most importantly, to the young audiences in the concert hall.

One of the most fascinating aspects of our art form is how people can come to relate with one another through the experience of listening to or performing music. Part of the aesthetics of El Sistema stem from realizing meaningful connections to narratives of feeling. What are the kind of experiences that we can create together? And how can we share them with those around us? It is truly a space of generosity, marked by ideals of profound solidarity and joy. This is part of what guides the mission of El Sistema--giving young people opportunities to relate to and learn from one another, build relationships, and imagine life-changing trajectories.

I also thanked Maestro Abreu for that same gift to us. For allowing us to enter into the narratives of El Sistema, and in doing so, inviting us to realize that in a space of generosity, anything may be possible.

We were all captivated by the performance. Over the years, the orchestra has grown to acquire a unique personality and palpable charisma. Beethoven was pushed to the limits. The Eroica lived and breathed in a space of increasingly wider dynamic ranges and more expansive phrases, always emphasizing the ground-breaking essence of the old-age narrative. It will be a recording that will generate a lot of interest among classical music enthusiasts.

One could readily feel Beethoven’s sense of angst and despair, of heroism and possibility. Today, Gustavo Dudamel and his orchestra took on the role of heroes, relating stories of passion and possibility to us all, and most importantly, to the young audiences in the concert hall.

One of the most fascinating aspects of our art form is how people can come to relate with one another through the experience of listening to or performing music. Part of the aesthetics of El Sistema stem from realizing meaningful connections to narratives of feeling. What are the kind of experiences that we can create together? And how can we share them with those around us? It is truly a space of generosity, marked by ideals of profound solidarity and joy. This is part of what guides the mission of El Sistema--giving young people opportunities to relate to and learn from one another, build relationships, and imagine life-changing trajectories.

I also thanked Maestro Abreu for that same gift to us. For allowing us to enter into the narratives of El Sistema, and in doing so, inviting us to realize that in a space of generosity, anything may be possible.

El Sistema Diary: Finding Mystic

During the last couple of days, I’ve heard from numerous people involved in El Sistema one word that resonates ever so strongly with the work we’ve experienced: that is, mystic. A word we don’t often hear, at least when describing the processes and outcomes of music education. After seeing a concert of very young musicians at Montalban, family members referred to the work as having a special mystic, “our children can learn to work together and believe in themselves,“ one mother said.

A recent New York Times article touched on the idea of an overarching mystic permeating El Sistema, citing an almost religious quality to the work of Maestro Abreu. This is very true, nucleos feel in many ways as sacred spaces, sanctuaries for the learning and teaching of music.

How does this manifest itself? As you enter a nucleo, there is music all around you. Upstairs, one orchestra can be working on Handel’s Water Music, while another plays an arrangement of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. Downstairs is a wind band playing through Tchaikovsky’s symphonies. In the room next door, cuatro lessons (a Venezuelan folk instrument) are being taught to anyone who might be interested. Other students are taking lessons in solfege, very young musicians are working on Dalcroze exercises. All happening simultaneously. One can hear music emanate from every classroom and carry into another, creating a kaleidoscope of sounds, all infused with an aspiring zeal. Every student in the nucleo is aware of each other’s musical activities, creating even deeper connections among themselves.

This is part of that mystic: the experience of being part of an endearing yet almost indescribable experience. That’s why students and teachers keep coming back, they instinctively know that music can offer the kind of intrinsic motivation and hope that few other activities can provide.

In El Sistema, music is seen in the context of what it can provide to the development of youngsters. And because music is one of the most demanding of all the art forms, it is the perfect vehicle to achieve this mission. Students are pushed to the limits. Middle-school age children can reach levels of musical accomplishment far beyond what is expected of that age group in any setting. Building a tenacious spirit is a way out of the stresses of both material and non-material poverty. Meeting extraordinary musical goals on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis is their measurement of success.

Indeed, inviting young people to believe in themselves might be perhaps one of El Sistema’s greatest contributions. The joy that this brings cannot be measured. It can only be felt--with the heart.

A recent New York Times article touched on the idea of an overarching mystic permeating El Sistema, citing an almost religious quality to the work of Maestro Abreu. This is very true, nucleos feel in many ways as sacred spaces, sanctuaries for the learning and teaching of music.

How does this manifest itself? As you enter a nucleo, there is music all around you. Upstairs, one orchestra can be working on Handel’s Water Music, while another plays an arrangement of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. Downstairs is a wind band playing through Tchaikovsky’s symphonies. In the room next door, cuatro lessons (a Venezuelan folk instrument) are being taught to anyone who might be interested. Other students are taking lessons in solfege, very young musicians are working on Dalcroze exercises. All happening simultaneously. One can hear music emanate from every classroom and carry into another, creating a kaleidoscope of sounds, all infused with an aspiring zeal. Every student in the nucleo is aware of each other’s musical activities, creating even deeper connections among themselves.

This is part of that mystic: the experience of being part of an endearing yet almost indescribable experience. That’s why students and teachers keep coming back, they instinctively know that music can offer the kind of intrinsic motivation and hope that few other activities can provide.

In El Sistema, music is seen in the context of what it can provide to the development of youngsters. And because music is one of the most demanding of all the art forms, it is the perfect vehicle to achieve this mission. Students are pushed to the limits. Middle-school age children can reach levels of musical accomplishment far beyond what is expected of that age group in any setting. Building a tenacious spirit is a way out of the stresses of both material and non-material poverty. Meeting extraordinary musical goals on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis is their measurement of success.

Indeed, inviting young people to believe in themselves might be perhaps one of El Sistema’s greatest contributions. The joy that this brings cannot be measured. It can only be felt--with the heart.

El Sistema Diary: Nucleo Sarria (Day 2)

The stories are real, it is truly a miracle. The passion and energy that emanates from young Venezuelan orchestras is mesmerizing. After our journey here in Venezuela, I know that my life in music will never be the same. At Nucleo Sarria, a community based initiative founded by Rafael Elster, we played through Arturo Marquez’s fiery Conga del Fuego. The youngsters also taught me some of their own national music, Alma Llanera and Chamambo. I felt being part of their own stories, their pride, their inextinguishable joy.

The students have a constant desire to acquire new knowledge. To realize a brighter present and future, to grow beyond music. Maestro Abreu’s vision for music as a catalyst for social transformation is at work at Sarria. His young musicians and their teachers are leading a new renaissance in music education. It is a privilege to witness this work first hand and to be inside the sound of that blessed space.

It is clear that the children see themselves as something larger than themselves. El Sistema has given them exceptional role models-- teachers that work tirelessly to redefine their student‘s sense of self-worth and potential; to provide them opportunities to experience beauty on a daily basis. It is that kind of implicit responsibility and purpose that drives their connection to the larger mission of El Sistema. “It is very hard work, but one has to make it personal or else our mission would never work,” Elster said.

There is something very special about working with orchestras in Venezuela. The children lead rather than follow the music. Everyone is part of the team, there aren’t any boundaries or hierarchical spheres in this framework. The musician’s at the head of sections aren’t necessarily the best players. A model where competition is non-existent constitutes an ideal space for El Sistema. Of course, that doesn’t mean that children can’t aspire to claim a coveted spot as part of the national orchestras, but rather, through a process where collective virtuosity stems as an outcome of individual skills, musicians grow and thrive, reaching even higher levels of musical achievement. They come to experience music through a vision that is guided by a spirit of solidarity. And this same spirit, provides them with a new family within the nucleo: a safe-haven to learn, socialize, and feel valued.

Their music is rendered through a transfixing kinesthetic quality (one can see that this process starts early on, as evidenced by their strong early childhood programs centered on movement and expression). It is a larger community of practice, a network within the orchestra, of mutual support; and of a new joyful reality. This is all reflected in the aesthetics of the music-making.

Indeed, one of the beauties of this work is how teachers envision the potential and life trajectories of their students. Najaneth Perez has been working at Sarria for over 7 years, she knows that her students are capable of accomplishments far beyond their own imaginations, in music and in life (there are no distinctions here, these two constitute one indissoluble dimension). And that’s why she works incessantly, listening to and perfecting them in the outside patio, amid the weather and the elements. Because she believes that she can make a difference. Every one of her students matters, every note means something, and it adds up. After all, it is personal.

El Sistema Diary: Nucleo Montalban (Day 1)

Today at Montalban, one of El Sistema's flagship nucleos, a 10 year-old musician told me, "el Maestro, wants us to learn and play la cuarta by the end of the month." Puzzled with curiosity, I asked, which fourth? "Tchaikovsky's fourth," he said. Last week, Maestro Abreu invited the Montalban children's orchestra to perform for the members of the LA Philharmonic during their recent trip to Caracas. They joined a 305-piece orchestra in playing the symphony's last movement, by heart. And now, they have an enormous task ahead of them, a complete symphony, one of the most challenging pieces in the orchestral repertoire.

Today, my colleague David and I had the opportunity to work through the first movement with the young musicians. A working rehearsal, their playing wasn't note perfect, but yet profoundly compelling. We heard music-making that was full of creativity and charisma. As I stood before them, it was as if the young musician's were telling me their own life stories, their aspirations, and their dreams--through their art.

There are no limits to the extent of possibility in El Sistema. The young musicians at Montalban know this. As you walk through the corridors of the building, (an austere yet welcoming space) posted on walls, one can observe a multitude of press clippings and concert photographs. A reminder of what has been accomplished thus far and where the group might be headed. "Children's Orchestra Travels to Europe, ""Young Musicians Captivate Simon Rattle," "The Children's Orchestra: Role Models for the Future."

Throughout our day, we saw among all age groups, a level of artistic commitment and work ethic that would parallel the kind of engagement stemming from our own country's conservatories. In Montalban, there is a healthy seriousness about the work at hand, a desire to achieve excellence among all levels of musical abilities, and above all, an extraordinary feeling of joy and devotion for music and for the community that helps create it.

El Sistema has a strong culture of visiting artists. And today we experienced a beatiful exchange. We saw nucleo teachers encouraging their students to take advantage of our presence on site. Some of us worked with youth orchestras, others with choirs, and early childhood education. In a flexible ecosystem of teaching and learning, we shared our best with each other. And we recognized one another as family.

Today, my colleague David and I had the opportunity to work through the first movement with the young musicians. A working rehearsal, their playing wasn't note perfect, but yet profoundly compelling. We heard music-making that was full of creativity and charisma. As I stood before them, it was as if the young musician's were telling me their own life stories, their aspirations, and their dreams--through their art.

There are no limits to the extent of possibility in El Sistema. The young musicians at Montalban know this. As you walk through the corridors of the building, (an austere yet welcoming space) posted on walls, one can observe a multitude of press clippings and concert photographs. A reminder of what has been accomplished thus far and where the group might be headed. "Children's Orchestra Travels to Europe, ""Young Musicians Captivate Simon Rattle," "The Children's Orchestra: Role Models for the Future."

Throughout our day, we saw among all age groups, a level of artistic commitment and work ethic that would parallel the kind of engagement stemming from our own country's conservatories. In Montalban, there is a healthy seriousness about the work at hand, a desire to achieve excellence among all levels of musical abilities, and above all, an extraordinary feeling of joy and devotion for music and for the community that helps create it.

El Sistema has a strong culture of visiting artists. And today we experienced a beatiful exchange. We saw nucleo teachers encouraging their students to take advantage of our presence on site. Some of us worked with youth orchestras, others with choirs, and early childhood education. In a flexible ecosystem of teaching and learning, we shared our best with each other. And we recognized one another as family.